Calzone Breaks Things

Exploring memory, reverse engineering, and fuzzing.

Reverse Engineering Myself, Part 1: amsi-breakpoint.dll

I recently completed FOR710, a SANS training course that dives deep into reverse engineering malware with Ghidra and various other tools. I found it hugely rewarding, but it was also clear to me that this is the kind of skill that gets rusty very quickly if you don’t keep at it.

Over the course of my career, I’ve written various pieces of software that might uncharitably be called malware. Part of the reason I took FOR710 in the first place was to understand what my binaries look like from the defensive perspective (I also thought it might help with black-box vulnerability research).

So, why not combine the two? By reverse engineering things I’ve written in the past, I can hone my reverse engineering skills. At the same time, I hope it will improve my understanding of the artifacts I left behind in code that was trying to be stealthy. That’s the idea, anyway.

For this first article in the series, I’ll be revisiting the AMSI breakpoint proof of concept I showcased in Frida vs. AMSI - Beyond Prototyping. I wrote that PoC to showcase a technique for evading EDR, but didn’t make any attempts to obfuscate the code itself. You can refer to the previous article to see the source code of the original tool. I won’t be referencing or reproducing it here, as the point is to infer what the DLL does without access to the original source code.

This should be very easy to reverse engineer, so let’s consider this a bit of a warmup!

Initial Analysis

I applied only the most basic obfuscation before analysing amsi-breakpoint.dll. I compiled it with gcc -s to strip debugging symbols, and then ran strip on it for good measure. Then I loaded it into Ghidra and analysed it.

Ghidra easily identified it as a binary that was compiled with GCC. Compiling a Windows binary with MingGW GCC is a little unusual compared to using native Microsoft toolchains, and might be an early red flag for a malware analyst. There was also a single error about missing MinGW relocation tables, presumably because it’s a stripped binary. Ghidra complained, but seemed to analyse it without issue.

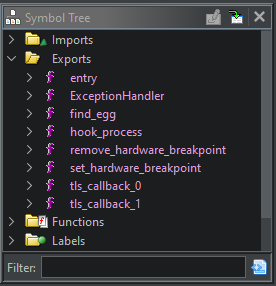

Interestingly, the binary still contains a bunch of named functions in the export directory even though I stripped it!

A little reading indicates that MinGW will actually export everything by default when you use it to create a DLL, not just DllMain(). This was news to me! Apparently you need to include this annotation:

__attribute__((dllexport))

When you do that, all of the functions you didn’t annotate will be hidden by default. I didn’t want to make things too easy on myself, so I did that and recompiled it.

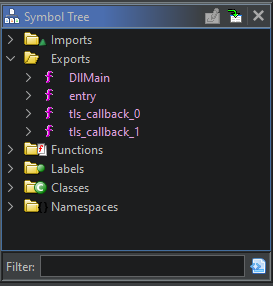

Much better!

Finding the Entrypoint

We can still see the DllMain export in the screenshot above. Since this a DLL and there’s nothing else in the export table that looks interesting, it’s a safe bet that this is going to be the entrypoint to our user-generated code. Still, in the interest of thoroughness we might want to confirm that this is indeed the main entrypoint for the binary.

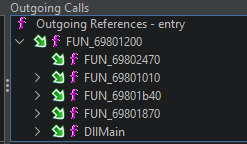

CFF Explorer shows that the ImageBase of the DLL is 0x6980000, and the AddressOfEntryPoint field is 0x1350. Within Ghidra, the pseudo-mapped address 0x69801350 corresponds to the entry symbol. So that’s our program entrypoint. Exploring outgoing references from there, we can see DllMain is ultimately invoked from the entrypoint:

We can assert with a fair amount of confidence that DllMain is the start of user-generated code, even if that wasn’t obvious already. We’ll bookmark it for easy reference and begin investigating it in more detail.

Analysing the Entrypoint

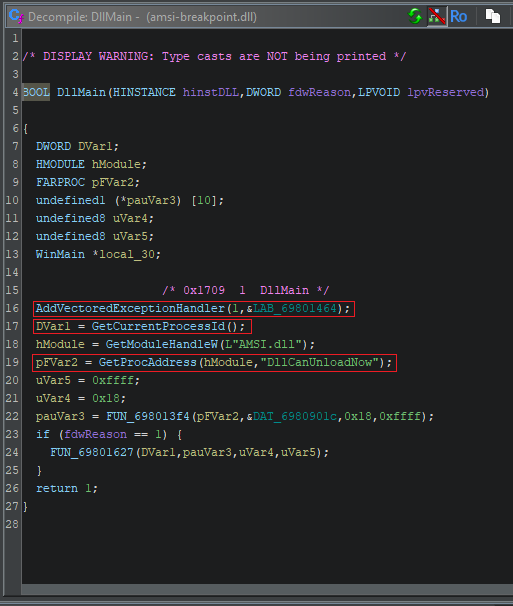

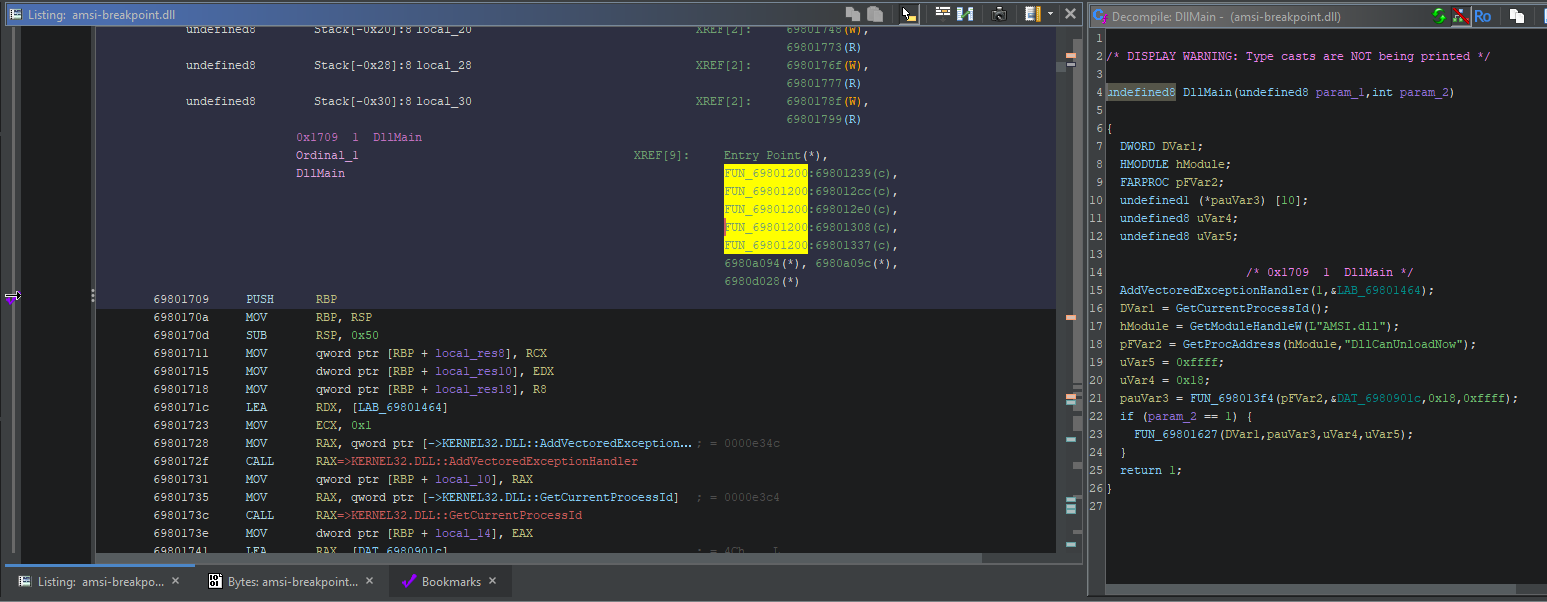

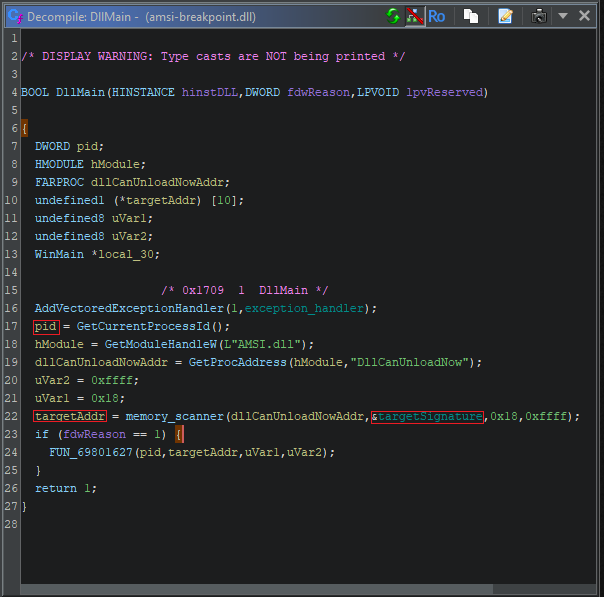

Here’s what we have to work with:

(click the image if you can’t see it very well)

(click the image if you can’t see it very well)

Reverse engineering often requires us to delve into the disassembly, but the decompiler output for this binary isn’t actually bad. Ghidra has automatically identified the Windows API call invocations, so there are only a few user-defined functions we’re not sure about the provenance of. We can make things even clearer by annotating the correct arguments and return value for DllMain():

We can already infer a few things that are happening here:

- We’re adding a Vectored Exception Handler, so presumably this DLL is expecting to handle an exception at some point. It’s common for malware authors to use a VEH as a way to trigger a payload.

- We’re getting the current pid, along with a handle to AMSI.DLL. We might therefore assume that some kind of process manipulation will take place.

- We’re looking up the address of a specific symbol within AMSI, DllCanUnloadNow(). According to MSDN, this is just a standard function that is exported by DLLs that are to be dynamically loaded.

We can guess that the purpose of this DLL is to interfere with AMSI somehow, probably for the current process. However, the exact mechanism is still unclear. We have three avenues to explore:

- LAB_69801464: This is the pointer passed to AddVectoredExceptionHandler(), containing the function that’ll be used to catch exceptions. It’s very likely this is where the actual AMSI bypass will occur.

- FUN_698013f4: This function is passed the address of DllCanUnloadNow(). It’s also passed a pointer to a hardcoded string of bytes which we can’t immediately identify. It’s unclear what it does.

- FUN_69801627: This function only executes if fdwReason is 1, or “DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH”. That is to say, it executes when the DLL is loaded. Therefore, it’s probably responsible for performing some kind of setup.

Analysing LAB_69801464

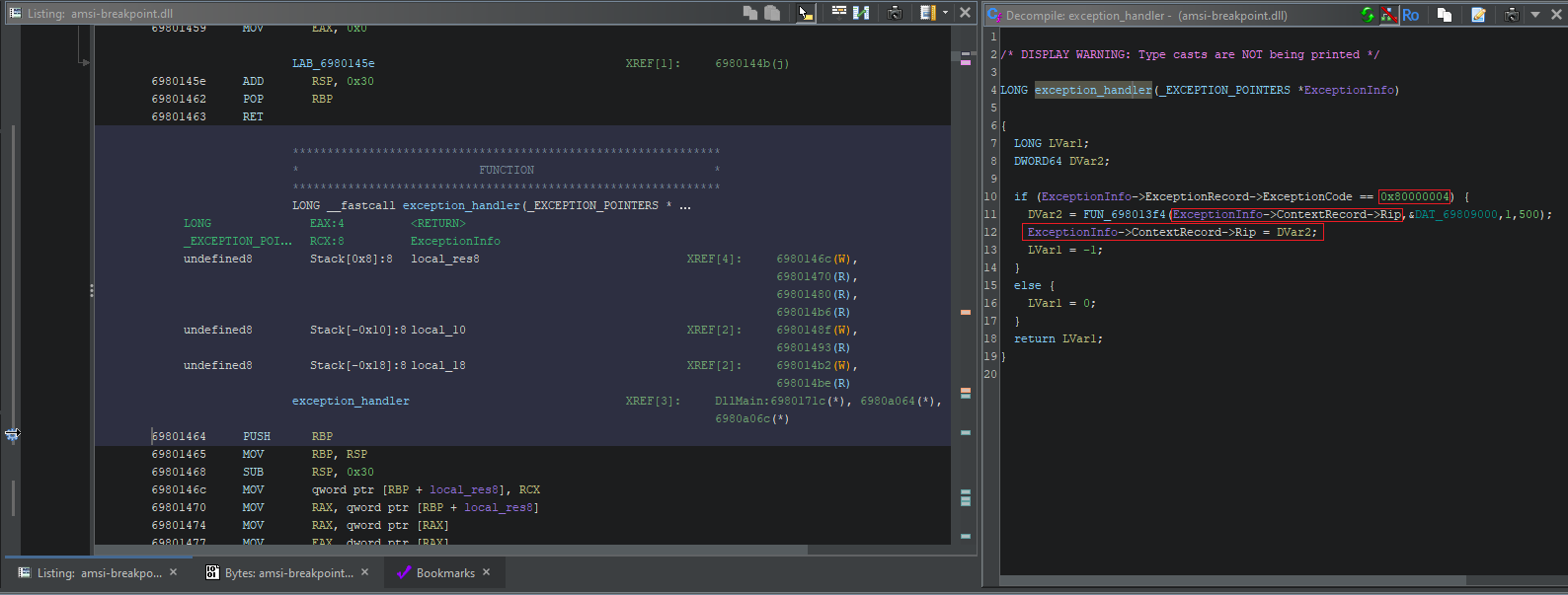

Since we’ve assessed that this symbol is where the AMSI bypass is likely to occur, this is where we’ll start. We already know it’s a VectoredHandler, so we can annotate the function with the correct arguments and parameters:

(click the image if you can’t see it very well)

(click the image if you can’t see it very well)

Since it’s so well-annotated, this is actually pretty straightforward to analyse. First of all, we’re checking for exception code 0x80000004. This is the exception code for EXCEPTION_SINGLE_STEP as per MSDN, which immediately tells us that this VEH is expecting to be triggered by a breakpoint.

We can also see another call to FUN_698013f4, which we saw previously in DllMain(). Here’s what it looked like back then:

pauVar2 = FUN_698013f4(

dllCanUnloadNowAddr, // pointer to DllCanUnloadNow()

&DAT_6980901c, // pointer to a mystery buffer of hardcoded bytes

0x18, // size of argument 2

0xffff // 65535

);

Here’s how it’s being called now:

DVar2 = FUN_698013f4(

ExceptionInfo->ContextRecord->Rip, // pointer to current instruction

&DAT_69809000, // pointer to a buffer which contains 0xC3

1, // size of argument 2

500

);

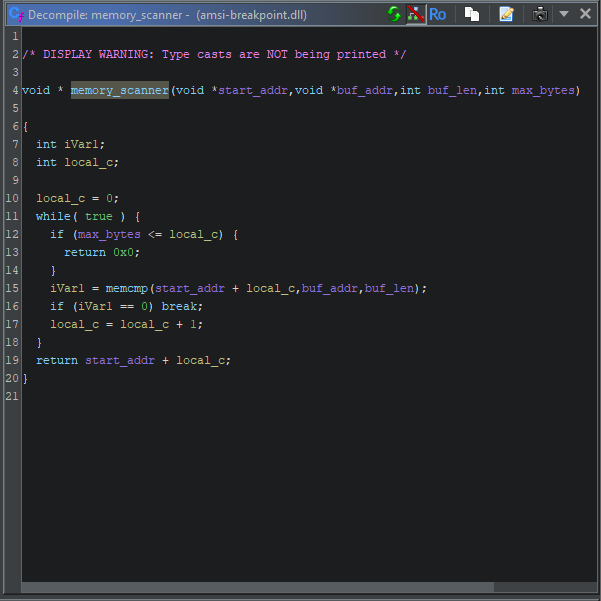

FUN_698013f4 also has a return value, which must be a memory address since the VEH uses it to overwrite the value of RIP - redirecting execution to that address. Even without analysing FUN_698013f4 ourselves, we can probably make a guess at its purpose: it’s a memory scanner.

You pass it a memory address and a sequence of bytes. It returns a different memory address; the first instance of that sequence of those bytes in the scanned region. The final argument is probably the maximum number of bytes to scan. We can annotate the function as such:

Armed with this information, we can guess what this exception handler does. When it is triggered by a breakpoint, it scans the current function for the next RET instruction (opcode 0xC3). Then it redirects execution to that instruction, ensuring that the body of the function is never executed. It’s a patcher, one that works without ever modifying memory.

Analysing FUN_69801627

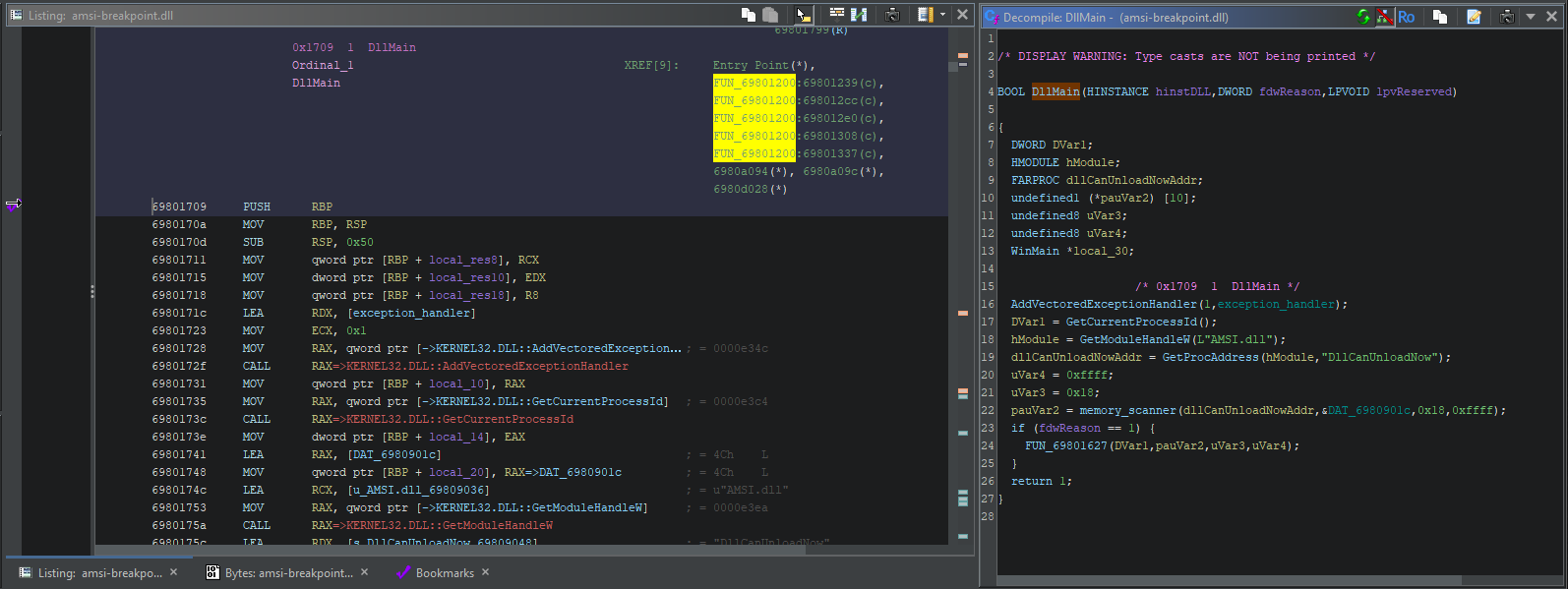

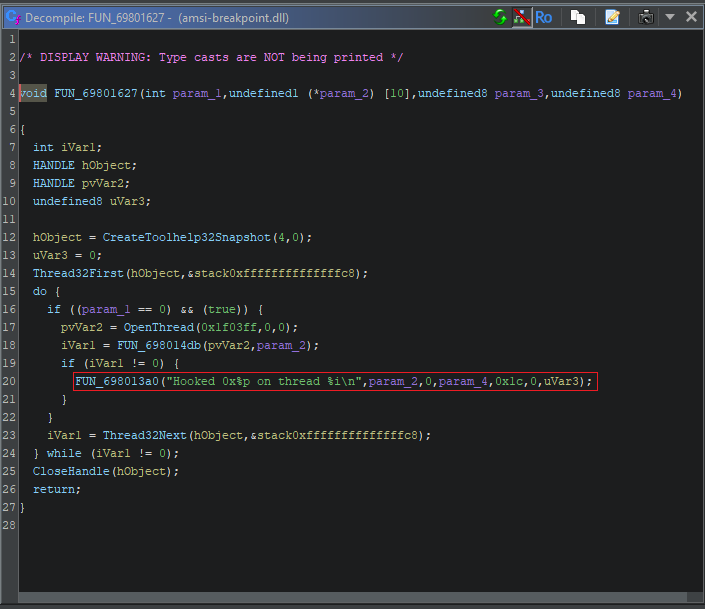

Let’s return to DllMain(), which looks a bit different now that we’ve introduced more context.

(click the image if you can’t see it very well)

(click the image if you can’t see it very well)

Most of the program is now fairly clear:

- We already figured out that FUN_698013f4 is a memory scanner and renamed it accordingly, so there’s no need to spend any more time on it.

- We also know, broadly, that the purpose of this DLL is to short-circuit the current function whenever it receives an EXCEPTION_SINGLE_STEP.

- We can guess, from context, that the function(s) it’s meant to be short-circuiting are related to AMSI.

We can assume that FUN_69801627, the setup function we identified earlier, is responsible for setting those breakpoints in the first place. But how, exactly? Let’s start from the call to memory_scanner().

Now that we know how it works, we can see that it starts from the address of DllCanUnloadNow() and scans forward into the executable code of AMSI.DLL. It’s searching for a specific sequence of bytes; we can now infer that those bytes correspond to the signature of the actual function it wants to patch.

Let’s rename variables accordingly to make that clear:

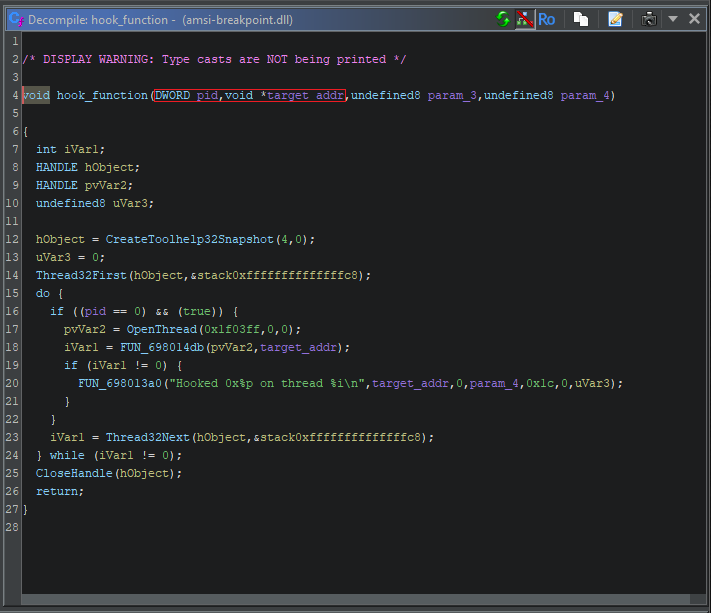

FUN_69801627 is called with the PID of the current process and the address of the function we want to patch. It also gets passed the 3rd and 4th arguments from memory_scanner(), which makes less sense, but let’s take a deeper dive and see what we’re working with.

Remember when I said I wasn’t trying to be stealthy with this one? Thanks to a debug print statement left in the function, we can immediately see that we’re on the right track. It’s clear that the purpose of this function is to hook a memory address.

We can also see that Ghidra has gotten some of the auto-generated parameters wrong. These first two parameters should be a PID and a pointer based on what we saw in DllMain(), so let’s fix that.

Thanks to helpful annotation of Windows APIs by Ghidra, we can get the gist of what’s happening here. There are calls to CreateToolhelp32Snapshot() and Thread32First(), a popular technique for enumerating threads within the current process. It seems like we’re iterating over every thread, getting a handle to it with OpenThread(), and then invoking FUN_698014db on it.

Analysing FUN_698014db

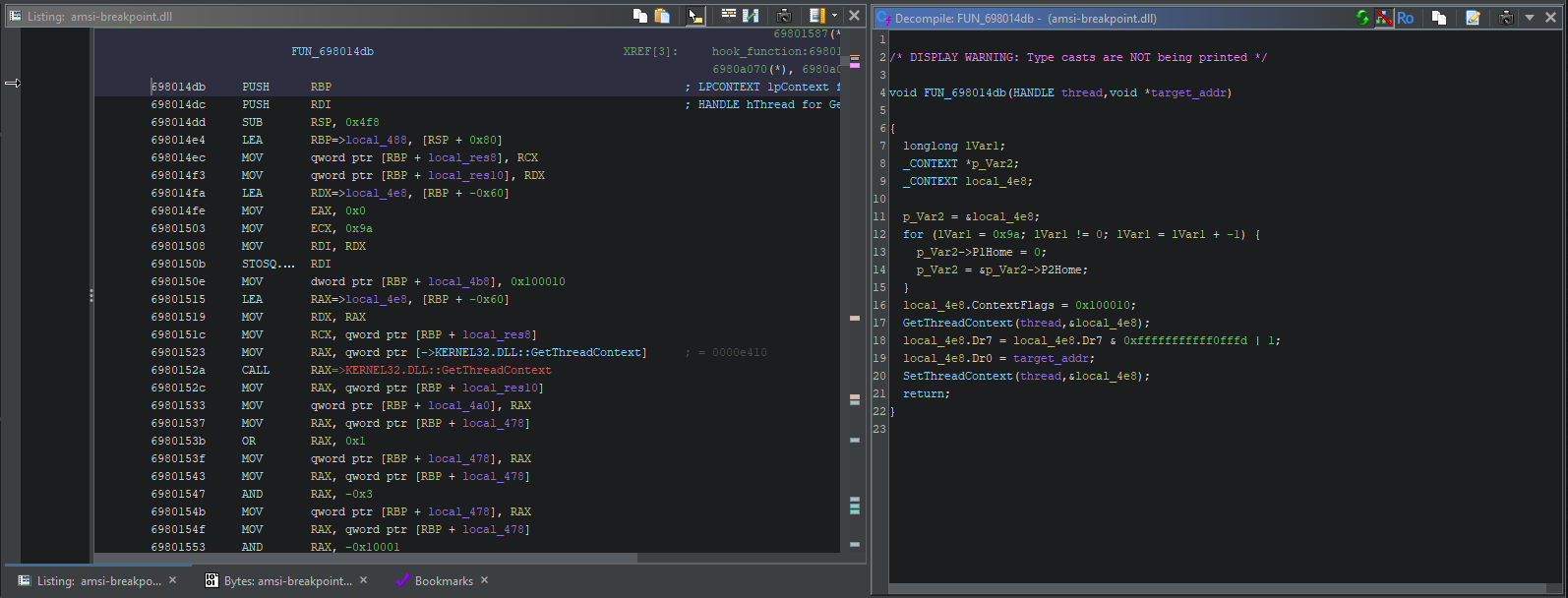

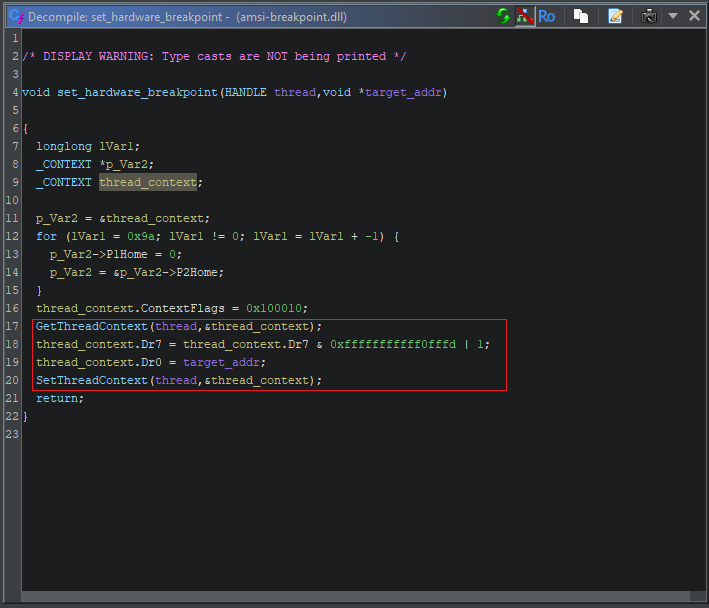

It seems like FUN_698014db is where the actual breakpoint creation occurs - it gets passed a handle to every thread in the current process, along with the address of our target function. Let’s take a look. I’ve already annotated the arguments, since we know what they are.

(click the image if you can’t see it very well)

(click the image if you can’t see it very well)

It might actually be hard to figure out what’s happening here without delving into the disassembly, but Ghidra has come to our rescue once again. It has automatically identified calls to GetThreadContext() and SetThreadContext() for us. These are two Windows APIs that can be used to manipulate the registers of a running thread.

Thanks to that, we can see that values are being assigned to the Dr0 and Dr7 registers… and that one of those values is the address of the function this DLL wants to patch. A quick google shows that Dr0 and Dr7 are debug registers used to set hardware breakpoints.

The Dr0 register is used to hold the address of the breakpoint, and the Dr7 register holds various bitflags that are used to configure, enable and disable breakpoints.

Conclusion

With that last step, we have the final piece of the puzzle. We now know exactly how this DLL works:

- It scans memory starting from DllCanUnloadNow(), looking for the memory address of some function within AMSI.DLL.

- It places a hardware breakpoint on that function, ensuring it will trigger an exception every time it is reached.

- It registers a VEH to catch that breakpoint, which then short-circuits the function to prevent it from firing.

The only thing we don’t know is which exact function within AMSI.DLL is being patched. We could make some educated guesses based on common AMSI evasion techniques. We could use a debugger to figure out exactly where that breakpoint gets triggered. If we wanted, we could even load AMSI.DLL into Ghidra and perform a memory search ourselves, since we know the exact sequence of bytes that the DLL is searching for.

With limited obfuscation and a fairly straightforward control flow, analysing this binary was a breeze. I didn’t need to do any dynamic analysis or reverse-engineer any deobfuscation routines, and I didn’t need to dive into the disassembly at any point. Still, it was fun to take apart something I made!

I’m planning for this to be the first in a series. I’ve written a fair bit of “detection avoidant” software over the years - mostly as learning exercises, though some I’ve actually had the opportunity to deploy in red team engagements. I’m looking forward to sinking my teeth into something I actually designed to be stealthy!